One fish No fish

Sunday 13 February 2011 During a surf trip through the Kei, a nostalgic Chris Mason is keen to go fishing after seeing huge catches in old photos that adorn the walls of the house where they're staying, but after a miserable yield, he begins to realise that the two eras are fishing poles apart. BTW Do you have a classic old photo of you or a family member with a huge fish ? Email us

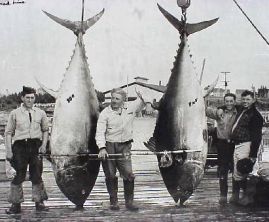

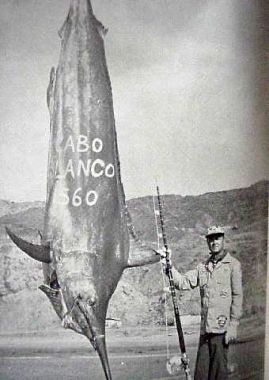

The cottage on the coast must have been 50 years old. High wooden rafters stretched above polished driftwood fittings, old laughter hanging in the musty air. Sepia photographs of sun-browned faces festooned the walls – washed out images of a time when there were more trees, and more time to go on holiday.

More fish too, it looked like. Men and boys in dark shorts hefted big fish to their chests, eyes burning with pride. Gillies – that uniquely South African tradition – stood to the side, or helped to hoist big hauls. This place, hidden along the Wild Coast of the Transkei, was fishing heaven.

We had a fishing heaven once, deep in the thickets of the South Coast, Kwa-Zulu Natal. I grew up hearing my grandfather’s tales of heroic fights with giant fish. Faded photos of smiling family members with over-sized catches also hung on our walls. I still go there, to the cottage he built nestling between wild banana and milkwood, although the house has changed, as everything does.

I went fishing at dawn the other day. At 4.30 am, the sun peaked over the horizon. By ten to five, a massive burning ball of red floated above the sea, the colour diffused by the dawn mist; painting the whole place a lucid orange glow. My dad joined me, nostalgic with memories of fishing with his dad on this beach

We knew there were fish around. The Khans had been around last night. They have been parking on our land and fishing the beach since I can remember. They pulled a few fish out, and left late.

Walking on the empty beach in the tickling onshore, I could see where they had stood - faded footprints in the sand. The big driftwood tree made a perfect bench. Drawing closer, I saw the knife marks and sardine heads on the wood. But an empty sardine box also lay discarded, as well as a plastic packet and coke cans half-buried in a feeble hole.

I felt a strange twinge of sadness, seeing these thoughtless remnants on my favourite beach. The Khans are nice people, and this was innocuous, or was it? I stared at the pile of plastic and tin. It went deeper than just being a fisherman.

“That’s fishermen for you”, said my dad.

For people so connected to the sea, they sure left a lot of litter. Maybe people saw the ocean as an infinite and eternal thing. Maybe this made them feel okay about trashing beaches. Maybe it was an old-school thing from before the time of environmental responsibility. Maybe fishermen are just human, and humans are good at taking, but not so good at giving, except for the crap they leave behind. It was perplexing.

We fished for a few hours, standing knee deep in the shallows, casting past the shorebreak. There were lots of nibbles from little black-tail, as they neatly trimmed the sardines off our hooks.

An old, heavy Ouma and her grandson stopped by. She sat on the driftwood, happy to catch her breath. The boy was about nine, and very interested in our fishing. He watched us closely, proudly recounting that his dad used bigger hooks, and had caught a really big fish. After ten minutes of watching us cast and re-bait he said to his grandmother, “They are not going to catch anything.” She smiled at us as if to say, “he’s just a boy” and told him to hush, and that fishing was about patience. He furrowed his brow, unconvinced.

My dad’s rod bent with the weight of a fighting fish. He reeled it in, and the grandmother shouted “Kyk! Oh ja. Dis n meneer!”

He brought it to us, a beautiful Zebra fish, maybe 1.5kg. “Are you going to eat it?" The boy asked excitedly, forgetting his scepticism in the thrill of the catch. “No,” my dad replied, “Too small. I am going to put him back.”

That was the only fish we caught, although we fished a few times. Where was the plentitude of fish from my grandfather's stories?

Back in the Transkei, I was eager to fish. The first day I saw several fishermen, with their tackle boxes, rain jackets and long rock-fishing rods. Every time I asked them “any luck?” they grumbled and shook their heads. Some blamed the rain, some the wind, and one said it was the wrong season. My friend’s mother had a more resolute answer, “There are no fish here. We’ve been coming for years and I have never seen anyone catch anything.”

But what about the pictures on the wall? We were far from the city, deep in the Wild Coast. This sea should be teeming with life.

The last time we fished, we almost caught something. In the brown shallows, my friend hooked a shad, and reeled it in. The fish fell off the hook and he jumped around trying to poke it with his rod. Laughing at his antics, I could not get there to stop it flopping back into the water.

So there are fish in the ocean. But the days of the giants are gone, and we are catching the rest. Someone close to me said we need to start thinking about fish as sea life, not seafood. I am starting to think she’s right.