Shorty Tribute

Tuesday 24 November 2009 Shorty Bronkhorst and Ray Heard were best friends at school. Writing from Toronto in his sunset years, Heard wanted to share his thoughts on Shorty's passing.

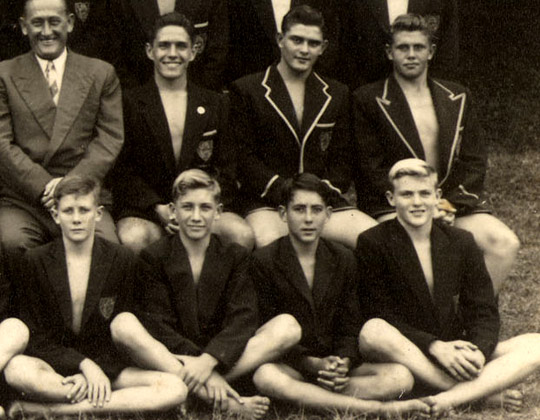

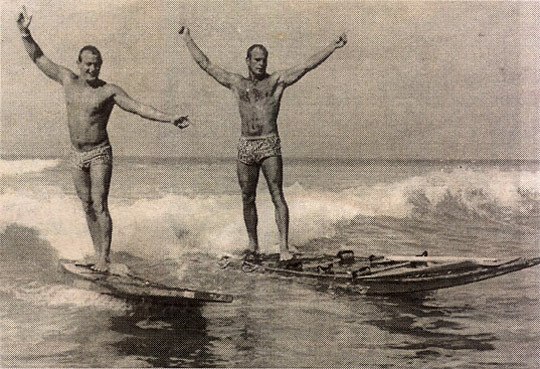

At Treverton and Durban High, Shorty and I were best friends. We only had one argument, which was over in a day or two. Shorty was a better surfer than me (though I still ride a long board) and was much tougher, though I gained some muscle fiercely competing against him on the beach and in the pool as a teenager.

Shorty was a champion diver and pole-vaulter on the rare occasions we were at school after classes; I did okay at middle and long distance runs against another formidable and brainy Beach boy all-rounder, Dux Coetzee, who is also gone. Shorty and I trained for games - indeed, for life - on the Beach, knowing that when you struggle through the white water it will be calm in the blue - at least until the next mountain slide pops up to (hopefully) take you in. As a cub reporter, I wrote a cover story for The Outspan magazine titled, They Deal in Lives. Its hero, naturally, was Shorty Bronkhost, photographed in colour on the cover leaping into the waves, muscles flowing, to save an upcountry farmer.

Shorty was a champion diver and pole-vaulter on the rare occasions we were at school after classes; I did okay at middle and long distance runs against another formidable and brainy Beach boy all-rounder, Dux Coetzee, who is also gone. Shorty and I trained for games - indeed, for life - on the Beach, knowing that when you struggle through the white water it will be calm in the blue - at least until the next mountain slide pops up to (hopefully) take you in. As a cub reporter, I wrote a cover story for The Outspan magazine titled, They Deal in Lives. Its hero, naturally, was Shorty Bronkhost, photographed in colour on the cover leaping into the waves, muscles flowing, to save an upcountry farmer.

Shorty and I had a lot in common. We were short. Our Dads never returned from the last just War. This meant we resented the rich boys whose fathers had stayed at home to make money. Because we were poor, we felt justified in stealing delectable tomato and onion sandwiches from the DHS Tuck Shop and avocados from nearby orchards. We both had beautiful, loving, hard-working single (and war-widowed) Mums, Cherry Bronkhorst and Vida Heard, both of whom laughed a lot despite their situation. Occasionally we would nick Cherry's Chesterfields, given her by a US captain friend on those grey-painted and numbered warships that would ply to and from the Korean war zone. We nicked some of her Old Brown sherry too.

The differences between us were that I worried more than Shorts, who always took life as it came. I read more books, and was more interested in politics, which he regarded (rightly) as a scam for scoundrels. Looking back, it's fair to say, our characters were complementary, making us quite a formidable team at times.

As you may have gathered, Shorts, my brother, Ant, and I really went to school not in Mooi River (at Treverton) or up on the Berea (at DHS) but on South Beach, and were always protected by older lifeguards like Chookie Saltzman, the Jardine brothers and my special hero, Roy Alloway, who went to Oxford and fought against apartheid as a lawyer on his return, and ended up, as I recall, in Australia. In our lives, nothing was more important than surfing, whether by body, Surf o Plane (Shorts could kneel on this type of rubber cushion in the biggest surf), Crocker surf ski or Hawaiian - or Aussie, long banana-shaped - board.

Because we could not at first afford them, we borrowed huge, hollow boards, which were finless and leash-less and made of Masonite over plywood frames, with Bostik to keep it all stuck down. These antique relics leaked massively, so a board could weigh 100 pounds when it took water and it was a lethal, dreadnought-like weapon if it hit bathers after we had fallen off. It had a special bung at the bottom, to draw off the water. It was so big it had to be left on the beach after dragging it from the surf. We could afford boards - only second-hand ones- after we earned money collecting those inflated rubber Surf o Planes from bathers and, using our boards, paddling barracuda and shark bait (live shad), clutched between our feet, way out beyond the tip of the Pier, while what we ungraciously called Hairyback anglers yelled, Verder! Verder! Sometimes we would add to our flimsy solvency by finding coins rolling down the beach on a high tide. Nothing pleased us more than to take our mothers out to dinner on the proceeds of our beach labours - always steak and mushrooms - at a posh restaurant, delicious Madisons near the railway station, or one in the cinema district, like the grillroom at the Playhouse, on Friday nights.

At Treverton, while tough Shorts protected me from notorious bullies, I would help him with essays. We rode horses together at Treverton, notably a white mare, Stella, who bit and kicked us, and a stallion, Tom, who had a more relaxed canter. The school dog, Tigger, would latch on to the tails of cows it chased, and get swung wildly to and fro, and thoroughly kicked. We went for long walks in the veld, through deep dongas and on koppies amid the forgotten graves of British Tommies who fell in the Boer war; sometimes we found and killed snakes with knob-kieries.

We fell prey, almost universally, to bilharzia, from swimming in the stagnant pools of the Mooi River where the snail-borne organism lurked. We played Army verus Navy football - a game in which every boy at the school took part. We also played Afrikaner games like kenneky, bok-bok and klei-lat, though drew the line at finger-trek. We had marbles galore, and would fool around and bunk out in the dead of night to roam the village of Mooi River at term's end. If caught, we faced six of the best.

We loathed the headmaster, Peter "Ploddy" Binns (because he had frog eyes, which blinked incessantly - though he did wake each and every boy with a touch on his shoulder even on frozen mornings). Even if at times Binns seemed to treat Shorts like a favourite, he took delight, after literally licking his lips and flexing his Malacca cane, in caning the bare bums of pre-teenagers after cold showers - and Shorty was his particular target; his bottom would be black and blue for months. That was more than a generation before an enlightened, democratic dispensation under Nelson Mandela outlawed corporal punishment throughout South Africa.

Shorty, unlike me (I had only two girl friends), was always a ladies' man. The beautiful Norma Tayfield was one of his loves while I unsuccessfully pursued her younger sister. I recall that, at a Saturday matinee, a girl in the row ahead of us, Lynette Springer, suddenly whipped round and hit Shorty on the head with her heavy handbag (with an old, heavy domestic iron strategically stowed in it for the purpose) for allegedly feeling her up from the row behind - something Shorts could rarely resist doing. Though he (and Ant) were frequently caned by sadistic prefects and masters like Binns at Treverton and at the DHS boarding house. Blackmores, I always talked myself out of punishment, which nurtured skill helped me in journalism later.

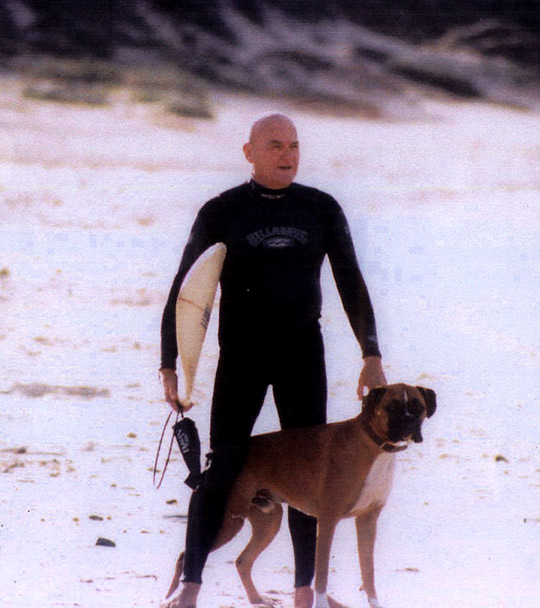

After DHS, I went to University in Bloemfontein, where they bullied me for being Engels, and Wits in Johannesburg, while working first on The Friend and then the Rand Daily Mail. Shorts, to my envy, stayed on the Beach, as a professional lifesaver, and then had a stint as a commercial traveller (with surfboard stowed in his hatch-back, for instant deployment away from work if the "slides were play"). He later toured Africa and Europe in surfboard-laden mini-buses. He and friends were reputed to have bought a hearse in London, the only vehicle they could lay hands on; and he proceeded to scare the hell out of Londoners by travelling in the coffin; and wierdly sitting up to look around. In those days, seat belts were not compulsory.

We last saw each other in 1956 when, recently married, I spent a few days in Durban with him.

Shorty, by all accounts, lived an exciting, happy life during which he seldom left his beloved surf. I went to Harvard, then Washington, London and Canada to cover Presidents, Pime Ministers and too many assassinations, riots and wars - not to mention the moonshot which coincided with Teddy Kennedy's more riveting Chappaquiddick. Toward the end, we renewed occasional contact via email while he was at J-Bay through Aige. I deeply regret I never made it back to see him and relive, however fleetingly, our years of friendship. I planned to do that next year.

But, in a way, my memories of the Beach from roughly 1947 to 1953 are more precious than any recent visit might have been. I say that because, to me, Shorty Bronkhost, my best friend ever - who trod the whole course of boarding-school at my side - never grew old. (Reading with a torch under the blankets at Treverton, Peter Pan was my favourite book).

With nostalgic thoughts of a lifelong fellow surfer, and admirer of the legend that was Shorty, and, as you observe the solemn lore of the waves and paddle out today, I say: Go well! You will have puckish company out there.