Coriolis and Upwelling

Monday 4 April 2011 After his first instalment on the thermohaline circulation of the currents, Dr Drew Lucas aka Captain Ahab returns to tell us more on the wind-driven circulation of the ocean (in two parts). Here is the first rapier-like jab of Ahab's gleaming harpoon of knowledge.

Hey guys, welcome back. If you missed the first post about the thermohaline circulation of the ocean, check it out … you might find that it provides a little useful background for what we will discuss in the next two posts - the wind-driven circulation of the ocean.

The currents of the upper kilometer or so of the ocean are controlled by the wind, but in a way that is not obvious from common experience. To understand how the wind drives the currents of the upper ocean, we need to think a bit about the rotation of the earth.

Turn, turn, turn. As you know (I hope!), the earth rotates around its axis, making a complete rotation in one day. Isaac Newton was one of the first people to realize that this rotation had a profound influence on movement across the surface of the Earth.

Newton had come up with a law, based on the work of Galileo, that states that once an object is in motion it will stay in motion (and going on the exact same trajectory) unless a force acts on it. This phenomenon is known as inertia and the law is Newton’s Second Law of Motion.

What Newton realized was that inertia only works relative to a particular point of view. We can call this point of view a non-accelerating frame of reference. That is, if we were off in space just sitting there and some piece of space crap came sailing by us, it would move in a perfectly straight line at the exact same speed for as long as we could see it.

Now, picture getting on a merry-go-round. As you go around, you feel a force that wants to fling you off the thing. This force is a result of the acceleration associated with going around in a circle… that is, according to the Second Law, once you are in motion you want to keep going in the same direction and speed as you started with. If you want to follow a curve and go around in a circle, there then must be a force applied to make you change direction.

Well, as it turns out, being on a merry-go-round means you are in what we call an accelerating frame of reference. That is, your eyeballs (or whatever you are using to observe or measure a particular phenomena) are accelerating. In addition to eventually making you puke, this peculiar state of affairs leads to a peculiar effect on motion.

Imagine there is another dude on the other side of the merry go around. You have a ball, and you want to throw it to him. It shouldn’t be hard, bru’s only 2 meters away. You chuck the ball, but no dice… the thing just veers off to the left. You are pretty sure you threw it straight, but you just watched it curve away and fly off, nowhere near your friend. Of course, to him, the ball veered off to the right. But he definitely didn’t catch it.

I’m sure you’ve already figured out what’s going on here. You didn’t magically break Newton’s Second Law. Once you let go of that ball, it flew in an exactly straight line at a constant speed. However, YOU were accelerating (going around in a circle) so the ball appeared to you to curve. That is, to you, there appeared to be a force acting on the ball to make it accelerate (curve).

Bottom line: if you are on a rotating thing, motion moving according to the law of inertia will appear to you to curve.

{youtube}_36MiCUS1ro{/youtube}

The situation is exactly the same on the surface of the earth. Being on the turning earth means we are in an accelerating frame of reference. That is, if you throw a ball far enough (or a wind blows a current long enough) it will curve relative to the surface of the earth (and us watching it). It isn’t, in fact, curving… it’s moving in a perfectly straight line in an frame of reference relative to the cosmos. It’s that the surface that is on is accelerating, just like the merry-go-round.

As an example of the importance of being on this great cosmic merry-go-round, let’s talk how upwelling works.

When the wind blows, friction transfers momentum from the atmosphere to the ocean. We know the longer and harder the wind blows the bigger the waves. The same is true of the currents: the longer and harder the wind blows, the stronger the current. But what about the direction of the current?

We know from our merry-go-round example that it’s going to curve. If you work the maths through, you’ll find that the net mass transport (the movement of water) is exactly 90° to the left of the wind. At least in Cape Town. To your friend on the other side of the merry go round, in the Northern Hemisphere, it moves 90° to the right. This is known as the Coriolis effect.

For those of us (un)fortunate enough to surf in the Western Cape, it is common experience that the water is colder in the summer than in the winter. This is, of course, due to the strong south-easterlies that howl all summer.

Now that we understand the influence of the rotation of the earth on the wind driven currents, it is very easy to understand how upwelling works.

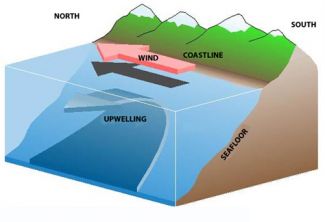

It is a common misperception that the upwelling is due to the offshore component of the wind (say the offshores at Dunes during a hard south-east, for example). In general, this is not true. Instead it is the southerly component of the wind that does it. Here’s how.

The wind, blowing from the south to the north, causes a net water transport 90° to the left of the direction of the wind. This means that the surface waters flow in the offshore direction. Now, in the open ocean, this wouldn’t do much… the water would just move horizontally, replaced by water further to the east at the same depth. On the coast, the situation is different. Replacement water can’t come from the east (cause it’s a beach, dude), so it must come from below. And down there in the deep of the deep south, it is cold, cold, cold my bru. That’s upwelling, and it’s all because our lovely blue merry-go-round keeps on spinning through the universe.

Next time, we’ll talk about the winds and how the control the great surface currents of the globe, focusing on the Benguela. Until then!

{jcomments on}