Conveyor Currents

Monday 14 February 2011 Dr Drew Lucas aka Captain Ahab is here to tune us some things - in a series of posts on Wavescape - that we might not know about the ocean, and he promises that we'll be even more amazed about the subject of our group obsession when he's done.

Since you are reading this, you love the ocean. As surfers, we are connected to the ocean in a visceral way. But, like all deeply complicated subjects, the more you know, the more interesting it becomes. I am here to tune you to some things you might not know about the ocean, and I promise you: you’ll be even more amazed by the subject of our obsession when I’m done.

Over the next few posts, I am going to cover some of the basics of large scale oceanography—the study of the fundamental behavior of the ocean. We will touch on the global system of currents and how they work, the tides, the basics of the ocean food chain, and finally wave physics and wave prediction.

First, a brief caveat: this is bound to be a bit bumpy — this is the first time I have tried anything like this. Any suggestions or criticism please feel free to leave them in the comments section. Just try not to be too much of a dick, bru. Now on to the good stuff.

The Global Ocean Conveyor

Without the ocean, we don’t exist. Leaving aside the very real fact that the first ~1 billion years of life was exclusively aquatic, and the fact that life in the sea is responsible for the oxygen in the atmosphere (we will return to this)-- the ocean, along with the atmosphere, controls the climate of the planet. It is a vast reservoir of heat, and it moves that heat from the tropics to the poles and everywhere in between. Think of Antarctica: Southern Africa would be covered in ice in winter if the ocean didn’t distribute heat. It is the global system of currents in the ocean, the central heating and air conditioner of the planet, that is the subject of my first two posts.

We are going to talk about too very different facets of the ocean circulation: the currents driven by the wind and the currents driven by density. The currents driven by the wind, the topic of the next post, dominate upper 1000m or so of the ocean, and include the Benguela and Agulhas Currents. The others, the deep ocean circulation, is controlled by something else entirely.

Density

First of all, we need to cover a basic facet of water—the colder and salty it is, the heavier it is. Cape Town waves ARE heavier than Durban waves, and that’s a fact: due to the temperature difference between Durbs and the Mother City (say 10 °C, although it can be much more) the water on the west coast is about 0.5% heavier than on the east. Doesn’t seem like much, really, except when you have an ice cream headache and you are taking a six-foot set on the head at Dunes. But, as we’ll see, density differences smaller than that control the currents of more than 75% of the oceans volume.

But that same image, we ourselves see in all rivers and oceans. It is the image of the ungraspable phantom of life; and this is the key to it all. -Herman Melville, Moby Dick

Think about oil and water… the oil floats on top of the water because it is lighter. Another way of looking at it is that the heavier water sinks below the oil. If you drip water on top of a layer of oil, it will sink straight through.

The thermohaline circulation

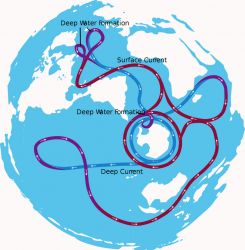

The Thermo (controlled by temperature) and haline (controlled by salt) circulation is the system of currents in the ocean that is due to differences in temperature and salt of content of the sea. This circulation is in the deep, dark, abyssal zones of the ocean, but it performs a remarkably important function. It controls the Earth’s climate on time scales of thousands of years.

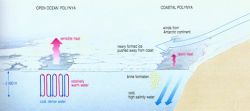

In the Arctic and Antarctic oceans, the extreme cold leads to the formation of sea-ice during winter months. When water freezes, nearly all of the salt is driven out. As you can imagine, sea-ice only forms when the water is brutally cold (around -2 C), and is therefore already very heavy. However, as the ice forms and the salt is left behind (brine rejection), the water surrounding the ice is now even heavier because it is saltier than the water below it, and so it starts sinking, starting a journey of thousands of years that could end in the tropics on the other side of the globe.

The wind in the polar regions is also important in creating very dense water. Strong, cold, and dry winds blowing over the surface ocean act to rapidly cool surface waters via evaporation. This process is called evaporative cooling and it is very effective in removing the heat out of the surface of the ocean. Of course, salt can’t evaporate, so the remaining water is both colder and saltier than the water below, and so it sinks.

This process is called Deep water formation and it is constantly happening in specific (and relatively few) areas in high latitudes during their respective winters. The water being constantly formed means that it must go somewhere, and that, somewhere, an equal volume of water must be slowly rising to the surface.

As it happens, the upward motion happens throughout the world’s oceans. This occurs over a much larger area than the narrow bands of deep water formation, and the rates of transport are incredibly slow. Nevertheless, it happens, and of course as that water moves vertically, it must displace the water above it, causing transport back to the poles. Thus the loop is closed, and the effect is this: heat is transported away from the warm tropics and to the frigid poles.

This is, as I’ve mentioned, a very slow process. This isn’t the cause of the Gulf Stream, for example, the waters of which keep the British Isles relatively temperate, even though they are roughly the same latitude of Moscow. This Global Ocean Conveyor is instead responsible for maintaining the distribution of heat around the planet on the time scales of millennia, and is the reason why the climate typically (before people, that is) changes quite slowly. It is the great, slow, climate regulator of the planet.

So there you have it: the great, slow currents of the deep ocean. Until next time, my friends!

{jcomments on}